Although the risk level for Southeast Asia is presently low, Thailand’s Health Ministry proceeded with the dissemination of an alert notice to the nation’s health workers yesterday, calling for ongoing vigilance in the face of the world’s deadliest Ebola outbreak since the virus was first discovered in the 1970s. Out of the five known Ebola subtypes, the strain involved in the current pandemic, first detected in March of last year, has proven to be the most lethal yet, claiming the lives of Western Africa’s two leading Ebola doctors.

The Lagos incident

Matters reached a more urgent level last week when a Nigerian government employee died from Ebola after first being diagnosed with malaria. Up until Patrick Sawyer’s death in Lagos on July 25, the latest outbreak was confined to the West African nations of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. Lagos is not only one of the world’s most densely populated cities, it is also a center of international travel, and the flights from its major airports are linked to 39 airports in 35 countries, including the United States.

In addition to concern for the broader Lagos population, Nigeria’s health authorities are desperately trying to locate Sawyer’s fellow passengers to screen them for a deadly virus that they might have contracted while on board the two Asky Airlines planes that Sawyer flew in. On July 30, the Reuters news agency reported that the airline had not released the passenger list for the two flights, while 20 of the 59 individuals who had contact with Sawyer following the flights have been tested.

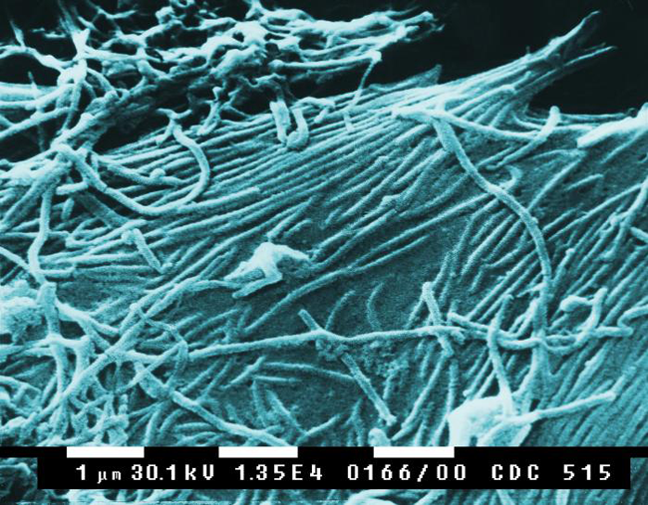

The virus

According to Canada’s CBC, witnesses aboard at least one of the two flights that Sawyer was on reported observing vomiting and diarrhea, causing concern for health authorities, as Ebola can be contracted through contact with traces of feces or vomit. Although Sawyer was malaria-positive, one of the issues with Ebola is that it initially mimics the flu-like symptoms of other viruses, such as malaria or typhoid, meaning that immediate detection can be difficult.

Aside from entering the body through open breaks in the skin, such as cuts, the most likely transmission points for the bloodborne Ebola virus are a person’s mucous membranes, such as the surface of the eye. Typically, people unknowingly transfer infected body fluids from their hands onto their mucous membranes; for example, someone rubbing their eye.

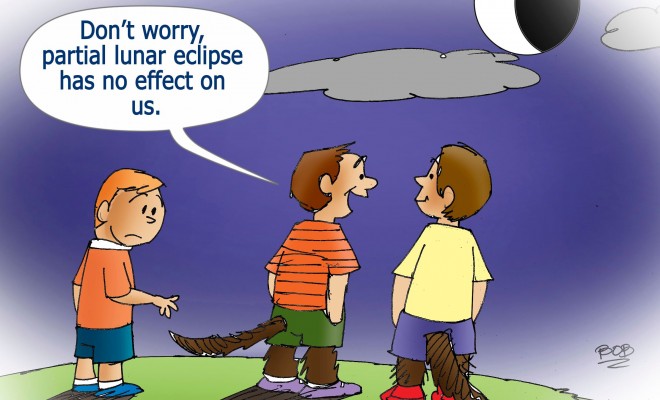

The virus has been described as brutal and efficient, with symptoms usually taking between one and three weeks to materialize, while death is the outcome for 90 percent of those infected. During the first week, the virus typically causes bleeding from mucous membranes—usually the intestines—and death occurs when the internal organs cease functioning. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients only become contagious once symptoms appear, and healthcare workers and relatives who are in close proximity to those affected are most at risk.

Unlike the flu, Ebola is not spread though casual contact—direct contact with body fluids or secretions, such as urine, blood, sweat or saliva, is necessary for transmission to occur. However, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada’s website, the virus can survive outside of the body for numerous days in “liquid or dried material” and we are still learning about important aspects of the virus. Infection through “small-particle aerosols” has been shown in primates and airborne spread among humans is not conclusive, but is “strongly suspected.” Additionally, the research on the website has found that the virus is “probably” transmitted from animals, with Ebola previously detected in domestic guinea pigs and certain bat species.

Governments respond

Further to the information disseminated by Thailand’s Public Health ministry yesterday, governments from other countries have also made their response public over the last week. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a Level 2 travel alert for travelers to Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, warning American citizens to “avoid contact with blood and body fluids of infected people.” Following the presentation of feverish symptoms from a U.K. citizen in Birmingham, who had recently flown home from Nigeria, the country’s Foreign Secretary informed the media yesterday that domestic “precautionary measures” had been implemented. However, as of July 30, the Thai, U.S. and U.K. governments have all acknowledged that the risk remains low for the populations of their respective nations.

Of course, in the affected African nations a more vigilant response continues, as Liberian, Nigerian, Guinean and Togo authorities screen outbound passengers, and Asky Airlines flights to Monrovia, Liberia and Freetown, Sierra Leone are temporarily inactive. Tarik Jasarevic, a WHO spokesman currently based in Sierra Leone, informed the media: “Every time there is an infection in a new location it is a serious development … You have to identify this person, test them, identify the contacts and follow them for 21 days.”

An arduous fight ahead

As of July 28, 50 healthcare workers, who usually wear protective biohazard gear, have died from Ebola, while approximately another 100 have been infected. To add to the grueling struggle in West Africa, two of the region’s foremost Ebola doctors are among the death toll: Dr. Sheik Umar Khan, from Sierra Leone, and Dr. Samuel Brisbane, from Liberia. On July 29, Bloomberg reported on the conditions of two overseas volunteers, including a U.S. doctor, who are being treated for the virus.

In addition to the Ebola virus, the African countries dealing with the latest pandemic face additional challenges, such as cultural issues—a U.S. charity found that 84 percent of the Monrovia residents they surveyed said they didn’t believe Ebola was real—and domestic problems like the nationwide strike of Nigeria’s doctors that was still running on Wednesday. In terms of containing the virus, David Heymann, a professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, stated this week: “The chance to stop it [Ebola virus] quickly was months ago before it crossed borders … but this can still be stopped if there is good hospital infection control, contact tracing and collaboration between countries.”

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Google+

LinkedIn

Email