Late last month in the Spanish city of Seville, nine cars went up in flames, as a result of protests against the sharing economy.

They were the property of private citizens, drivers for a peer-to-peer ridesharing app called Cabify. The blaze was the latest in an apparent string of retaliations against the so called “sharing economy.” Unregulated sharing economy companies like Cabify and Uber can undercut the heavily regulated taxi industry.

Meanwhile, Spanish taxistas have gone on strike. They’re protesting against competitors who don’t have to pay heavy licensing fees. It can cost upwards of $140,000 to operate as a licensed cabbie.

Over in Madrid, the city hasn’t issued new taxi licenses since 1978. That means they fetch high prices on the secondary market. In the past two years, Madrid has seen the number of drivers for companies like Cabify more than triple. And that has left conventional cab drivers feeling threatened and outraged.

“We’re worried about our jobs,” taxi driver, Ignacio Pico, told Bloomberg. He participated in a protest outside the Spanish parliament in Madrid. “They’re cannibalizing our industry.”

Drivers Stand Up to Uber and Co.

Cabify, a Spanish competitor to Uber, has echoed the Silicon Valley sharing economy party line. They say they have no intention of competing with traditional cab services. They insist on perpetuating the myth of the sharing economy: that the app only connects willing drivers with people who want to pay for a ride.

They’re not employees, so the company can transfer all risk and responsibility to the workers. The app, for example, doesn’t suffer a loss when the cars get torched. The workers do.

In essence, sharing economy apps like Uber and Cabify have hired “one half of the working class to kill the other,” as robber baron Jay Gould once said. In the meantime, sharing economy tech execs reap the financial rewards. They are protected from all responsibility.

The protests in Spain are only the latest example of the threat that the sharing economy presents to global working class communities. Anti-Uber protests have erupted in Paris and India, too, as the company aggressively continues to expand.

The Sharing Ain’t Caring Economy

A few short years ago, many people thought the new sharing economy sounded like a great idea. But things have unfolded in a way that some critics say shows an ugly economic reality.

Sharing economy apps like Uber and Airbnb promised to connect people. Users could exchange services like ridesharing and housing swaps. Such promise brought fresh hope to industries calcified under decades of regulations. Such regulations were restrictive to growth and innovation.

The apps also offered a way for workers to make money on the side. This was a great idea for a depressed economy where wages had stagnated and housing costs skyrocketed.

But the sharing economy mutated quickly. Far from solving these class problems, it now only seems to be exacerbating them.

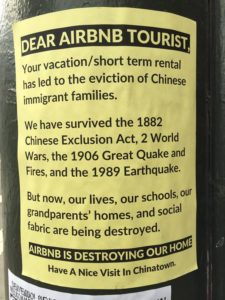

Airbnb has faced backlash for damaging local economies. What started as an innocent way for users to rent a spare room has become a platform for wealthy landowners to rent out full properties as vacation rentals. This drives up real estate markets and pushes local hoteliers out of business. The sharing economy isn’t what it sounds like.

Cities Fight Back Against Airbnb

In New York City, Airbnb’s biggest market, 30 percent of all “homeshares” are actually listed by commercial entities, not individual homeowners. Instead of renting apartments at market rates, these landlord companies are Airbnbing units as short term vacation rentals. That makes affordable housing even scarcer in a city where it’s already close to nonexistent. What are these “sharing economy” vanguards actually sharing?

About half of all New York Airbnb listings violate city laws. But many of those include listings by private individuals who are using the app the way it was originally intended–subletting their apartment for a week when they’re on vacation, for example, in the original sharing economy spirit. As New York cracks down, fines are going to the users, not the app.

Airbnb has also been shown to accelerate gentrification. It floods neighborhoods with its 80 percent white demographic, and fills residential buildings, often those with working class “charm,” as though they were hostels, to the dismay of legitimate residents.

San Francisco and Barcelona are also enforcing new Airbnb laws to combat the damage the aggressive sharing economy avatar is wreaking on local housing and hotel markets.

An anti-Airbnb poster in San Francisco’s Chinatown

In the Sharing Economy, You Can Work As Much As You Want

Like the “rideshare” platform Uber, whose brand seems to include accumulating terrible press by any means necessary, sharing economy apps like TaskRabbit or Amazon’s Mechanical Turk outsource small jobs to contractors not formally employed by the corporation. The presumed benefit of this kind of work is its flexibility. A house cleaner working for TaskRabbit can set their own hours, and work as much or as little as they want.

The problem is, because workers don’t have access to liveable wages even when they’re formally employed at a regular job, these sharing economy “side jobs” are not the luxurious monetizing of one’s down time that Silicon Valley billionaires would like you to believe. Many Uber drivers work round the clock trying to stay ahead of the fact that every mile they drive costs them money, too.

This model benefits those who own the app, but not the workers who support its operations. Uber is valued at $40 billion, and takes 20 percent of driver earnings. What’s left is barely enough for drivers to stay profitable after they pay for their own gas, insurance, maintenance, etc.

Former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich on the Sharing Economy

“A more accurate term would be the ‘share-the-scraps’ economy,” writes Robert Reich, who served as Secretary of Labor under the Clinton administration. “The big money goes to the corporations that own the software. The scraps go to the on-demand workers.” He goes on:

This is the logical culmination of a process that began thirty years ago when corporations began turning over full-time jobs to temporary workers, independent contractors, free-lancers, and consultants.

It was a way to shift risks and uncertainties onto the workers – work that might entail more hours than planned for, or was more stressful than expected.

And a way to circumvent labor laws that set minimal standards for wages, hours, and working conditions. And that enabled employees to join together to bargain for better pay and benefits.

The new on-demand work shifts risks entirely onto workers, and eliminates minimal standards completely.

In effect, on-demand work is a reversion to the piece work of the nineteenth century – when workers had no power and no legal rights, took all the risks, and worked all hours for almost nothing.

He says that sharing economy corporations like Uber and Amazon dodge responsibility for worker safety, social security, or minimum wages (to say nothing of livable wages), because they technically don’t employ them.

Welcome Back, Dickens

The sharing economy is creating a Dickensian working environment, as the Independent calls it, “creating a virtual ‘human cloud’ of ‘digital serfs’ that leads to a global race to the bottom for wages and benefits.”

Heavily regulated traditional workers are in one corner. Exploited sharing economy workers are in another corner. Tech billionaires are pitting them against each other. City governments are trying to watchdog the tech billionaires, but sometimes penalizing the people. The stage is set for perhaps even more explosive confrontations.

The results of these tense economic developments remain to be seen. The sharing economy may have been a good idea, but in the end, who will really benefit?

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Google+

LinkedIn

Email